FLOES OF TIME

We forget the body, but the body doesn’t forget us.

Us. Damn memory of the organs!

– E.M. CIORAN

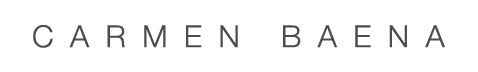

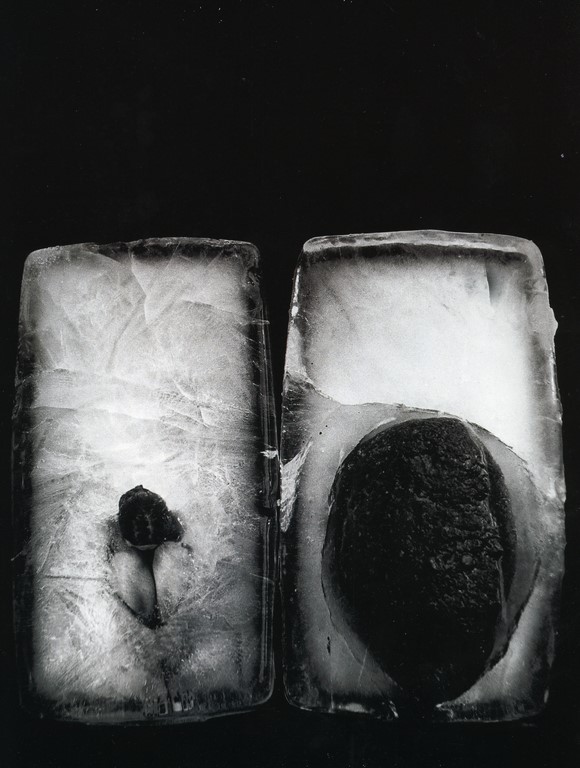

Inhabit (in) a body iceberg. Ice cream. A body touched by ice. Closed fragment. Closed body. Closed ice. Closed body in the ice.

To stay, to remain, even in what flows.

Practically the whole of Carmen Baena’s work is governed, in one way or another, by a capital idea, which, according to Michael Serres[1], constitutes one of the focal points of tension in contemporary society: to inhabit. An observable dwelling both in his sculptural production, formally related to a lyrical postminimalism linked to certain evolutions of land art, and in his work on paper, which, with the exception of photography – now in question – maintains a line of reflection very similar to that carried out in sculpture. To inhabit, therefore, to always inhabit, or to try it. Looking for a place: the house, the nest, the origin.

Such a discourse – such an obsession, one might say – around this dwelling, if one observes it well, seems to start, at least, from two different notions of this concept. Two conceptions that are but two sides of the same coin.

The first of them would be related to a reflection on space in a sense very similar to that expressed by the French philosopher gaston Bachelard throughout his vast work[2]: the interior space of the house, the nest, the hiding place… places where the body stays, waits, waits, lodges, shelters itself from the thing (res). Places of permanence, always for the delay. It is a question of locating oneself, a finding oneself, clearly related to the idea of origin. And it is that the house is always in Baena an origin: a place to inhabit and to remain, it is true, but also a place for the reencounter. A place of arrival that, at the same time, is always a beginning. The place of return, the home to which one always returns. And, in this sense, the place is space, but also time. Circular time in which every wound is origin… eternal return.

The second conception of inhabiting that it is possible to notice in the production of the sculptor from Granada is also linked to phenomenological thought. A conception that seems to obey the contradictory-and paradoxical-Heideggerian command to «inhabit distance»[3], whose most palpable mise en oeuvre can be observed in her series of sculptures and drawings-titled «nomads»: beings that «inhabit» that cheasmatic space that separates and unites two different places. Beings could be thought-condemned to err eternally, to neither remain nor stay. Beings for whom the place does not exist, or, at least, not as something «localized». For the nomad, the place, the home, is not something geological; its place is the distance, the space/time that distances/media between two places, as if it were eternally crossing a bridge-place par excellence of the chiasm-that does not lead to any concrete place. And perhaps its only place of permanence was the body, the body itself: the body that (inhabits) the distance.

To inhabit, therefore, always to inhabit…even the distance.

To stay, to wait, to delay, to remain… even in what flows.

Baena’s photographic work, presented in these Tempanos de tiempo, rather than constituting an ex-course to the rest of his sculptural production, stands as a dis-course and logical evolution of the latter, as a synthesis in which two elements are introduced which, although they had already been insinuated in past works, are now made explicit: time and the body. To the bachelardiano poetic space of air, water and dreams is now joined the space of time: the space of the body. The body of time and the time of the body. And by introducing these elements of reflection, Baena’s work is placed at the centre of contemporary artistic discourse, a discourse governed by reflection on the problems of time, but above all of the body.

It was Rosalind Krauss who, at the end of the 1970s, observed that modern sculpture, since Rodin, had been characterized by a constant search for temporality which, in some cases, such as minimalism, had been present in a profound reflection on the concept of time[4] A reflection that also points to the other «place» par excellence of contemporary art: the body. While it is true that the body has always been present in art as an element of the first order, it should be noted that, over the course of the last hundred years, and especially since the early 1960s, artists and thinkers have questioned with particular intensity the way in which the body had been painted and how it had been conceived. In the words of Tracey Warr «the idea of an «I» endowed with a stable and finite form has gradually been eroded, echoing the influential developments that the twentieth century has produced in the fields of psychoanalysis, philosophy, anthropology, medicine and science. Artists have investigated temporality, contingency and instability as inherent qualities of the human.

Baena’s photographic work is on this same path of reflection. It is a quite outstanding path, we will affirm categorically, if we keep to the subtlety and serenity with which such questions are approached here, both from the unquestionable aesthetic point of view, endowed with a formal purity deeply rooted in the classical form, closed in itself, stable and balanced-as well as from ladiscursive-acute, not at all superficial and full of nuances and implications that mean that the work is not exhausted in a first reading.

But what is an iceberg? one might ask. A hard fragment, absolute, like any other fragment of time. A fragment of stopped time? An iceberg of the body, one might say. Of a detained body? Of time stopped in the body. Stopped in the way it stops its becoming in still life, using the meaning that the term possesses in the English language: Still life.

Life at a standstill: icebergs of life. All the time concentrated in a small piece of ice. In a body iceberg.

And here comes the paradox: the body, temporal element by nature, stopped-sitll life. But how to stop the flow of time, the flow of the body?

Carmen Baena’s work starts from this dramatic contradiction: to say the unspeakable, to capture what flows, to stop it in its impossibility of stopping. And something like this is only possible through a vertical conception of time, a conception like that held by Henri Bergson, the philosopher of time, for whom everything is written in everything, as in that Library of Babel in which a single book contained the key to the entire universe.

For Bergson, the essence of being is precisely time, which lasts, which passes. The very thing about being is duration: being lasts in time. But the time Bergson speaks of is not the time of the sciences, of mathematics, of calendars, it is not the exterior time, of clocks, of minutes and seconds. This is not time, but its symbolic image: a clock through which seconds run is not time, but a codification of time, a representation. Because time cannot be measured or analysed, since in order to measure it we would have to stop it, divide it into moments, fragment it…sacrifice it. The time Bergson speaks of is very different. Real time, true time, time, is situated beyond appearance or offering itself to the eye, it is found inside, in the experience of what has been lived, in the consciousness of life. True time cannot be analyzed, nor can it be divided, because it is a continuous time, of indivisible continuity. An inner time, a time of pure duration, without precise contours, which melts and dilutes in itself.

An iceberg of time-an iceberg of the body-would possess, in itself, the whole flow of the concentrated universe, or what is the same: life stopped-dramatic contradiction.

Time cannot be measured…it cannot be said. And the body? Nobody knows what a body can do,» said Valery. «Nobody knows the time of a body», we can write here. Or better yet, following Bergsonian logic, «No one knows how long a body lasts.

It is about time, yes, it is true; but it is also about space, about place. Because the body, you could say, is a there, a «being-the-there», spatial, flowing. In front of the Hoc est enim corpus meum-This is My body; body without space, always summoned, expected, absent–, an allocution on which, according to Jean-Luc Nancy[6], the whole bodily culture of the West is erected, the icebergs of Baena, on the other hand, are, more than ever, spatial bodies, ex-placed, ex-cripted, completely inhabitable bodies.

To live in the body, inside it, closed and out, or to live with the body? That would be the key. Carmen Baena seems to keep the last alternative: to live with the body.

To be with the other, even more so when that other is the origin, the earth. More than ever, to inhabit with the other, to be with the other, when the other is-and here serves the enunciation of Félix Duque-the fresh ice-cream-ruin of the earth.

His being put to Work. His being-their duration-stopped: still life.

«And in the beginning was the body», one could write. And the body was rl origin. The origin of the body. The body of origin.

But what is the origin? Certainly not the principle. The origin is what, like a snake, is eternally revealed against time. All time is the origin of itself. Therefore: the origin of the body is the body itself. A body which, here stopped, on the other hand, remains a body, touched by ice, a cold body, which feels. It is not a completely intact body, apart from the dimension of touch. Still life. Still touche.

The body feels, the body is touched. Touched by the ice. By an ice that is much more than just solidified water. It is not just any water. It is that of dreams to which one always returns…the water was inhabited and will be inhabited-that every day is inhabited. Water of the amniotic: amniotic body. The original house, the house of origin.

The body as the room of time, of the earth. Ice floe of flesh. Bark that feels.

In -touch body with -touch. Cold, icy, and, at the same time, warm, full. Always present. Inhabited body, spatial…original in itself: body -origin, body -household, body -water, but also body -time, body -space.

Or what is the same: body – body.

Miguel Á. Hernández -Navarro

[1] Michael Serres: Atlas.Madrid: Cátedra, 2000

2] Gaston Bachelard; Water and Dreams. Mexico: Fondo de cultura Económica, 1989.

Pier Aldo Rovatti: Abitare la distanza. For un´etica of the linguaggio. Milan: Feltrinelli, 1994.

4] Rosalind Krauss: Passages of modern sculpture. A history of sculpture from Rodin to Smithson. Madrid: Akal, 2001.

5] WARR, T. «Preface», in The Artist´s Body. New York: Phaidon Press, 2001, p. 11.

6] Jean-Luc Nancy: Corpus. Madrid: Arena Libros, 2003.

EN LA CAMARA ANECOICA

Para Carmen Baena

La sangre es lo que suena

Si apagamos la luz.

Todos buscáis en los huecos un trozo

Exacto de vacío.

Fabricáis pianos cojos y mellados,

undís violonchelos en baldes de agua,

porque anheláis un tesoro de nada:

buscáis la materia prima del odio.

Pero se oye la sangre

Si apagamos la luz

Y encontráis siempre el sonido del tiempo

Entre las ramas de un pálido bosque,

Esas gotas de ira cayendo lentas

Desde los murmullos aburguesados,

Ese silbo lacerante del viento

Que os turba para que no me veáis.

Mirad dentro del círculo,

Estoy aquí, flotando

Desnuda, tranquila, lejos de todo,

En este témpano helado y eterno.

Pedro J. Miguel