OF SNOW AND TREES

– Come, enter my house.

It seems to tell us the work of Carmen Baena, inviting us to enter the intimate space of her dwellings.

The house as a shelter, as a warm refuge, as a metaphor for a protective environment, a place of refuge. The house as a metaphor for one’s own being.

Carmen Baena’s dwellings merge with a landscape in which the interior house is profiled as a lighthouse, as a promising goal, as a destination. From their houses with roots, rooted, solidly embedded in the ground, to the lightness of rain houses, decorated with feathers, ethereal; the house is repeated again and again as a symbol of the most intimate. Only by knowing ourselves of a place can we abandon them all, be nomads, move through spaces and materials, the artist seems to tell us.

Because there are aromas of travel in Carmen Baena’s work, winds that push us towards a private odyssey, towards an epic search for subjectivity.

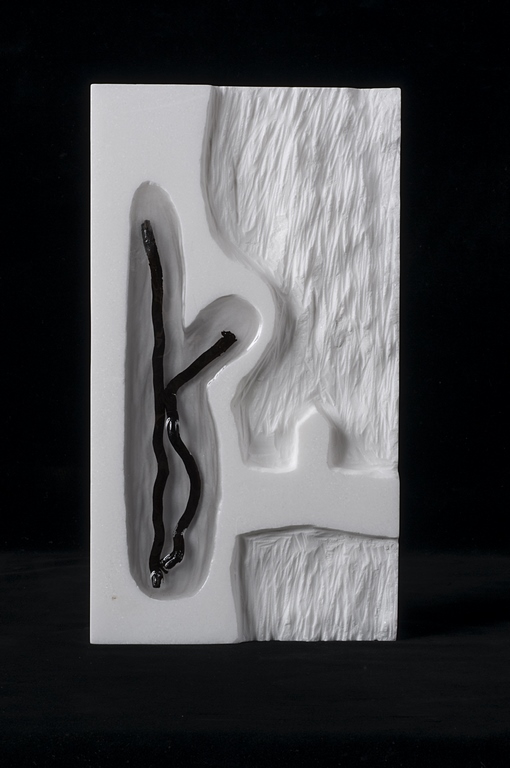

A journey that begins in his first works, where nature itself is the support, where, from materials found at random – fragments, sediments, stones -, nature adheres to sculpture, nature is sculpture. And that continues to transit until rising little by little towards what we could call the natural, the minimalist abstraction, the stylistic and aesthetic simplicity. Nature as an idea of nature.

As if in her passage from the most telluric and natural materials -wood, rope, mud-, of sinuous and organic forms, until reaching the white hardness of marble -of precise and snow lines-, the sculptor showed us the process of an investigation on herself, on the human conceived as intrinsically united to the natural, on her effort to find a place in the world, to build with her work a country where Carmen Baena lives, where she lives.

It is in this last abstraction where the spatial movement expands, becomes macroscopic, and the landscape enters the scene in a perfect tension between the minimalism of the work and the extension of what we want to show. The sculpture here includes mountains and valleys, extending the territory to be represented. A paradoxical geography, then, the more it encompasses, the more intimate it becomes, more stylised and dreamlike; a minimalism in which, and we resort to its reference author, Gastón Bachelard: «We will see the reverse of things, the intimate immensity of small things».

There is also a melancholic gesture heard through these sculptures, forceful and light at the same time. As if the author were immersed in an incessant remembrance of certain past images that insist on her, seeking her expression. As if an archaic muscular memory led her fingers and arms to sculpt the materials, until she managed to domesticate them in search of an interior landscape. A muscular memory that seeks, time and time again, the reunion with the idealized landscape of childhood. The domus, the house and the land.

And it is here where another feature of the sculptor’s personal evolution appears: as the organic gives way to abstraction, the originally hollow house closes in on itself, closes down, and appears before us, no longer accessible by means of braided scales, but as a fortress to be conquered.

Hence the almost mystical lyricism transmitted by his sculptures. Hence the internal space evoked by these snowy exteriors. A lyricism that takes us back to the inner fortress, to the castles of the soul, whose conquest is nothing more than a path of knowledge, of self-knowledge. The fusion with the divine, longed for by mystics, seems to be substituted in Baena by the fusion with nature and the earth, with the original territory from where the author’s particular biography arises.

It is here a secular, epistemological mysticism, which connects with a particular desire for the sacred as intrinsic to man, as an irreducible impulse that runs through our entire history, that puts wings to the house, that invests it with gold, gold, that projects it to heaven like the monasteries of Meteora, like the Hindu temples, to which some of her works allude. But also with the sacred interior, the temple as an intimate place of knowledge and expressive richness, the place where transparency barely veils what the exterior tries to hide, because Baena’s works express a special taste for the hidden, for a reciprocal relationship between the external and the internal, which feed each other, modifying their composition and appearance.

Closely linked to the sacred is the omnipresence of trees: Arboreceres. Treeing, in our language, means to become a tree, to take root? Carmen’s sculptures present an obsessive insistence on the presence of a sublimated, platonic tree, reduced to its woody structure; a tree inserted in the marble, minuscule, that imposes its humble biological forms to the classicism of the straight line.

Symbol of the sacred, the tree appears in mythology and culture as the center of the universe, as a representation of life, of sustenance, of the whole. Frazer, in The Golden Branch, illustrates the worship of the trees of mythical traditions from different parts of the world, placing the forest as a synonym for temple, to the point of pointing out how «among the Germans, the oldest sanctuaries were natural forests … Among the Celts we are all familiar with the cult of the oak druids and their ancient word for «sanctuary» we believe identical in origin and meaning to the Latin nemus, an open forest, which still survives by the name of Nemi.

Treeing, becoming a tree; the irrational, the instinctive, the sacred, nature as an incessant rebirth, are inserted in the work of Carmen Baena in the rationality of the geometry of the marble, achieving a magical harmony that transports us to a direct beauty, of a polysemic and ambiguous eloquence.

Transferred to the subjective investigation to which the work seems to us, alludes, the arboreceres of the artist show us a yearning of articulation without fissures, complex and harmonic, between the culture to which the marble refers and the biological spontaneity of the vegetable.

From our viewpoint as spectators, we contemplate these spatial texts as if they were writing, since their forms are impregnated with something magically narrative, as each piece seems to contain a secret history.

To walk through these landscapes is to enter into a singular and suggestive world, a rich Lilliputian universe that awakens our senses by reproducing in us deep, familiar sensations that refer us, without a doubt, to our own secret geographies.

– Come, enter my house, come.

Lola López Mondéjar